Reading Traces

Idea and Process

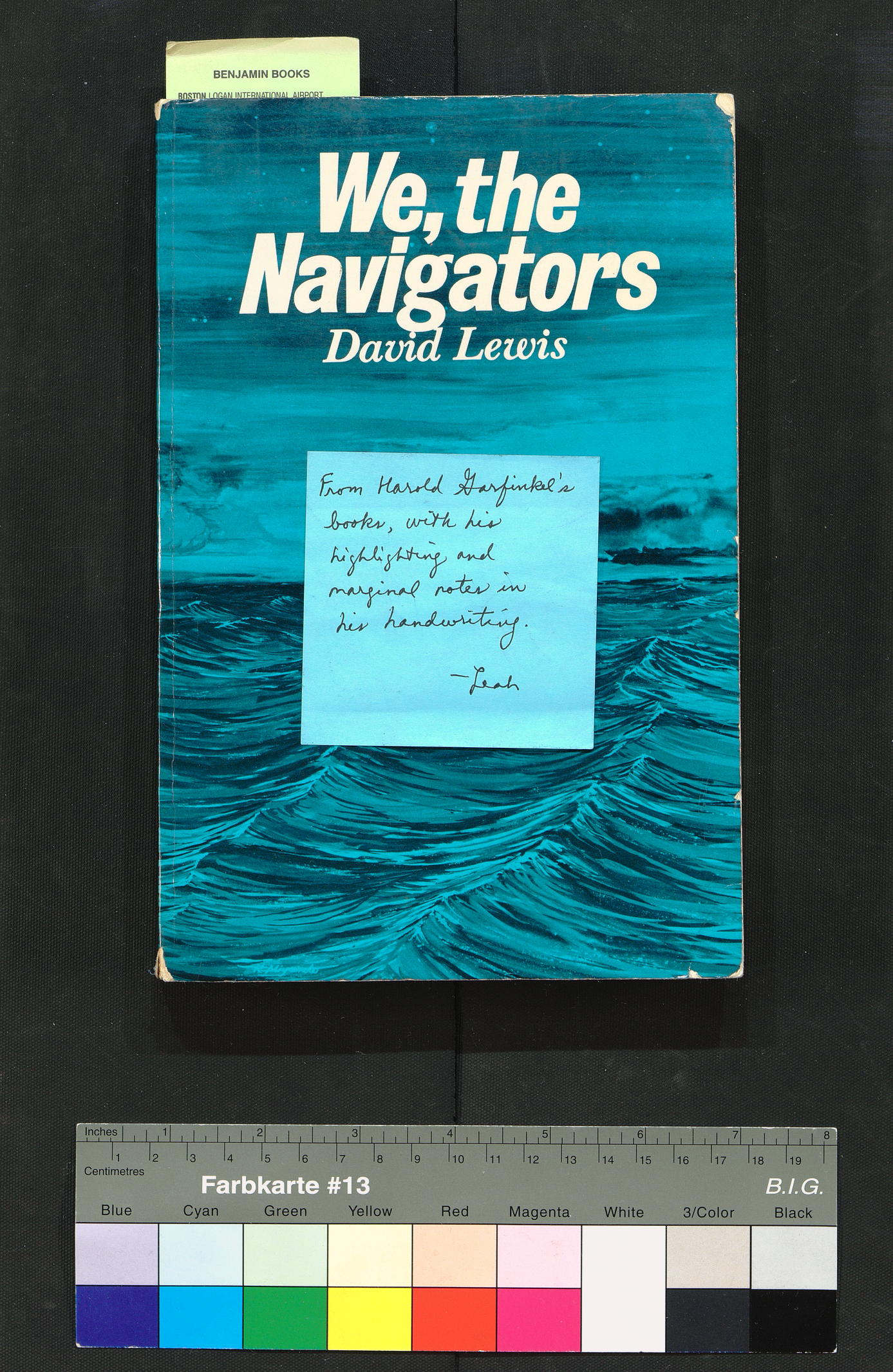

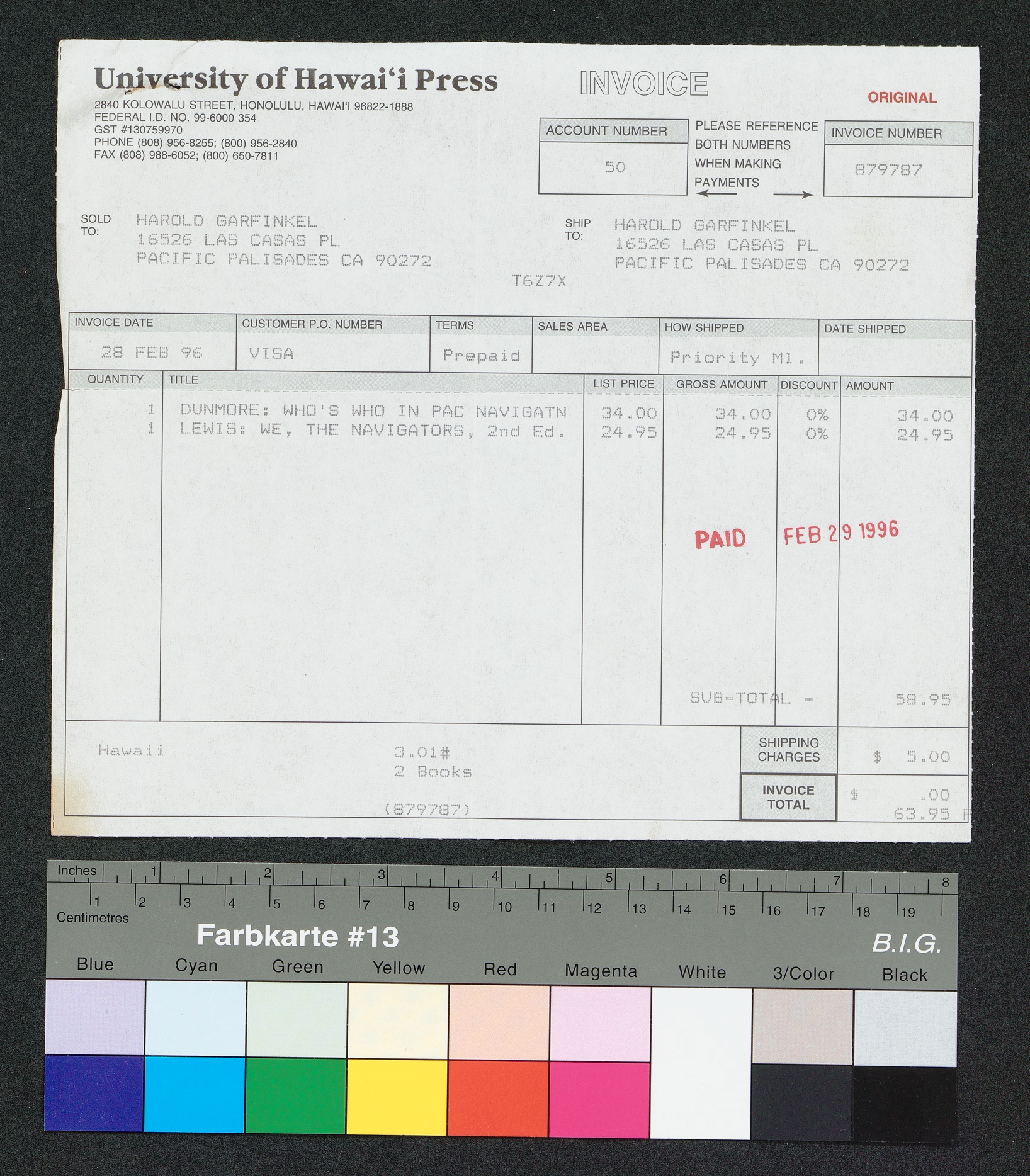

The Occasion Map Papers include a heavily annotated copy of David Lewis's book We, the Navigators. Harold Garfinkel not only added extensive annotations to this book but also preserved the purchase receipt as part of this particular collection of papers.

Garfinkel’s meticulous curation of his working documents was neither accidental nor incidental; it was an integral aspect of his research methodology. Anne Rawls, the current director and a former student of Garfinkel, highlights the significance of his curatorial practices with two key examples: his strong opposition to archival methods that involve selective document handling or rearrangement, and his creation of a photo album that documented his workspace and organizational principles, aimed at preserving his systematic approach.

Garfinkel made both direct and indirect references to We, the Navigators. A notable example is his discussion of “stick maps of Pacific Island navigation,” mentioned in his application draft, Notes Comparing Two Analytic Formats of Occasion Maps of Way Finding Journeys: ‘Documentary’ and ‘Essential Procedural’.

This connection offers an opportunity to unite several project goals in a single example: understanding Occasion Maps through digitization, exploring Garfinkel’s methodology, and applying best practices in Digital Humanities critically. During the digitization of the Occasion Map Papers, a key aspect of text-based activities in Digital Humanities had to be considered: text encoding according to the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) Guidelines. TEI Guideline serves as a standard for encoding texts, enabling the representation of features such as structural, topological, linguistic, orthographic, documentary, and semantic elements (cf. https://academic.oup.com/dsh/article-abstract/26/4/463/1055470?redirectedFrom=fulltext).

TEI is used across various disciplines with diverse approaches. Its applications are remarkably broad, spanning contexts such as drama analysis, codicology, linguistics, and scholarly editions, to name just a few. Furthermore, it is employed in the print industry too as raw data for publishing in various formats.

TEI is a community-driven effort. In 1987, the Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH) organized a meeting with 30 representatives from archives, universities, and humanities computing centers to bring order to the fragmented and inconsistent approaches to computational text studies that had emerged since the 1960s [footnote: https://www.cs.vassar.edu/~ide/papers/teiHistory.pdf]. To establish a common practice the group developed a set of principles to guide the process of developing encoding and exchange of literary and linguistic data. https://tei-c.org/Vault/SC/teipcp1.txt

CLOSING STATEMENT OF THE VASSAR PLANNING CONFERENCE

1. The guidelines are intended to provide a standard format for data

interchange in humanities research.

2. The guidelines are also intended to suggest principles for the

encoding of texts in the same format.

3. The guidelines should

a. define a recommended syntax for the format,

b. define a metalanguage for the description of text-encoding

schemes,

c. describe the new format and representative existing schemes

both in that metalanguage and in prose.

4. The guidelines should propose sets of coding conventions suited

for various applications.

5. The guidelines should include a minimal set of conventions for

encoding new texts in the format.

6. The guidelines are to be drafted by committees on

a. text documentation

b. text representation

c. text interpretation and analysis

d. metalanguage definition and description of existing and pro-

posed schemes,

coordinated by a steering committee of representatives of the

principal sponsoring organizations.

7. Compatibility with existing standards will be maintained as far as

possible.

8. A number of large text archives have agreed in principle to sup-

port the guidelines in their function as an interchange format.

We encourage funding agencies to support development of tools to

facilitate this interchange.

9. Conversion of existing machine-readable texts to the new format

involves the translation of their conventions into the syntax of

the new format. No requirements will be made for the addition of

information not already coded in the texts.In the case of the annotated copy of David Lewis’ book, TEI offered an opportunity to follow the reading traces of Harold Garfinkel. In digital humanities discourse, “reading traces” refers to the evidence of a reader’s engagement with texts, whether in physical or digital forms. These traces might include highlights, marginalia, notes, or even more subtle patterns like where a reader lingers on a page. By capturing, documenting, and analyzing these traces, researchers gain insights into how individuals or communities interpret and interact with literature, historical documents, or other textual materials. Such analysis can shed light on shifts in reading habits over time, variations in reader response across different media, and new pathways for scholarly interpretations.

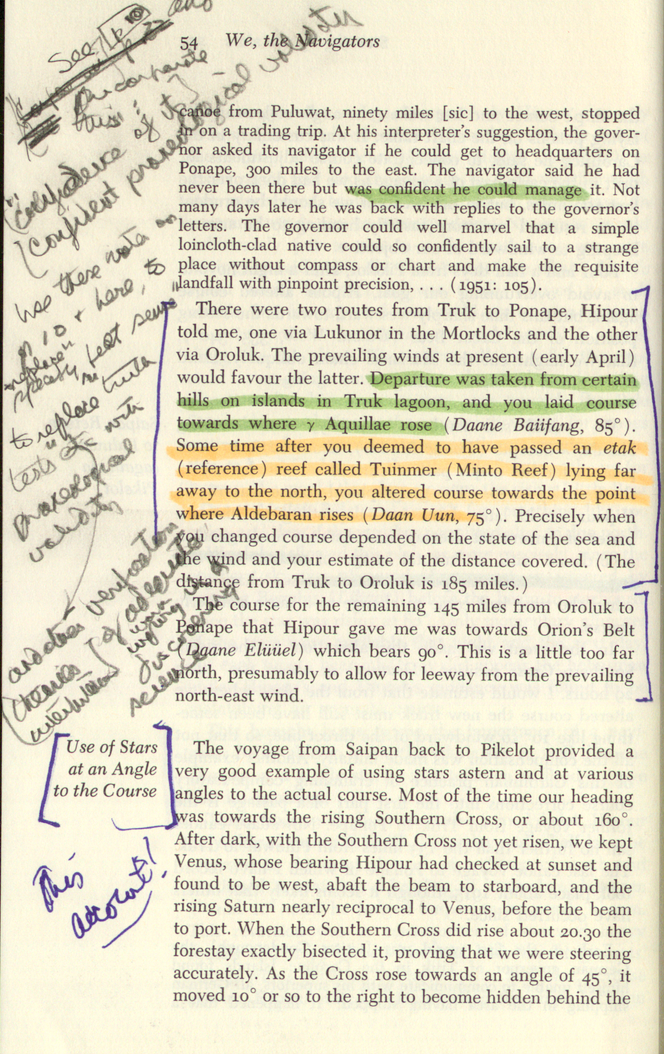

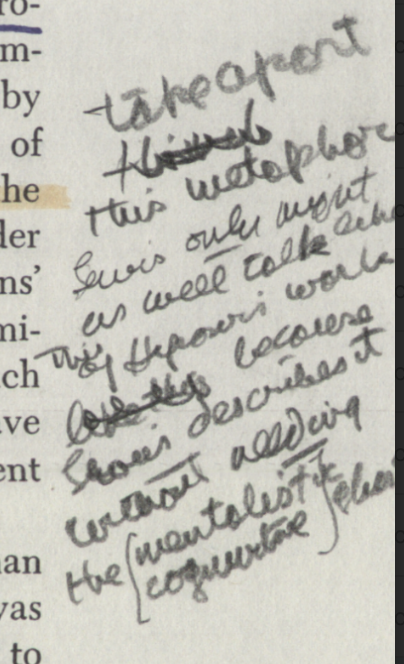

We, the Navigators, page 54. Garfinkel writes annotations as marginalia and uses arrows to expand, marks sections with big square brackets and highlights some sentences in different colors (right: code-snippet from the TEI-XML File)

In an alignment with the project’s ethnomethodological goals, the process started with examination of best practices of research in the area of reading traces.

Two particular approaches are given special focus: the Theodor Fontane Archive’s collaboration with the Urban Complexity Lab at Potsdam University of Applied Sciences on Fontane’s reference library, and the Beckett Digital Library Project, which offers a digital reconstruction of Samuel Beckett’s personal library— with transcriptions of reading traces and connections to his manuscripts.

With its intensive focus on reading traces, the Fontane Reference Library project has developed a systematic categorization of the traces, trying to shed new light on his engagement with texts. The main categories are Marginalia (e.g., comments, text corrections, translations), Markings (e.g., underlines, strikethroughs, highlights), Provenance Information (e.g., ownership stamps, handwritten notes), Additional Material (e.g., glued-in newspaper clippings), and a catch-all category called 'Other' for things like stains or dog-eared pages.

These categorial work taken as best-practice produced ‘troubles’ in two areas. On the one hand mundane, functional traces like cross-references and directives as in ‘doings’ are left out. Additionally function of any type of trace not defined, although they seem to follow a 'functional order' depending on its properties. Marking forms and types in Garfinkel’s traces exemplify this: arrows, brackets, asterisk, circles etc. seem to create a 'layer of meaning', which is not 'intrinsically integrated' into 'categorization work'. Encoding alone can only mark them as markings without unfolding their 'doings' as a layer of making sense of the text at the encoding level. To counteract that encoding concentrated on typology of shapes to at least list the specifics. Second area of ‘trouble’ here is the point of contact between these categories and the formalities of TEI. In its schema TEI offers no specific module for encoding reading traces but there are some elements which can be used to integrate categorial work on the traces with the affordances of TEI:

<additions>(msDesc module): Groups descriptions of all additions (e.g., annotations, stamps, seals) to a manuscript.

<accMat>(msDesc module): Describes accompanying physical material (e.g., loose sheets, booklets) tied to a manuscript but not part of its main structure.

<add>(transcr module): Marks short additions (words, phrases) inserted by authors, scribes, or annotators within the text.

<addSpan>(transcr module): Marks the beginning of a longer sequence (e.g., paragraphs, marginalia) added by a hand other than the original scribe. Requires coordination with<anchor>or<span>to mark the endpoint.

<note>(core module): Generic container for annotations or remarks (e.g., editorial notes, glosses). Can be specialized with@typeor attributed via@resp.Though generic, it can capture reading traces when scoped with attributes (e.g.,

@type="reader_mark").

<metamark>(transcr module): Encodes authorial or scribal directives (e.g., "move text," "insert here")—writing traces that guide production, not reading.

The TEI’s emphasis on elements like

<metamark> and <add> reveals a deeper categorial bias: it

prioritizes traces of textual production (e.g., scribal corrections, authorial insertions) over

reader-generated meaning-making. Ethnomethodologically, this mirrors Garfinkel’s

"seen but unnoticed" problem: the schema formalizes observable

actions (e.g., adding a word, circling a passage) but neglects the phenomenological

layer—how readers orient to

these marks as part of their ‘doings’ (e.g.,

cross-referencing,

annotating for later retrieval). For instance, a circled word might

function as a

reader’s emphatic trace rather than a scribal correction, yet TEI

lacks mechanisms to capture this intentionality without retrofitting (e.g., overloading

<note> with custom attributes).

This ‘trouble’ exposes how TEI’s schema, while meticulous about document structure, fails to formalize the interactional work readers do with traces. Garfinkel would argue that meaning emerges not from the mark itself but from how people use it—a layer currently "seen but unnoticed" in markup practices. The schema’s document-centric model reduces the ‘accountability’ of reading traces to their material form, divorcing them from their use-practices. Consequently, encoding risks rendering traces literally (as shapes or locations) while missing their indexical functions.

The TEI schema presents several functional limitations for encoding textual interventions:

- The

<add>element cannot span paragraph boundaries, forcing fragmented representation of continuous additions.

- While

<metamark>specifically encodes authorial/scribal directives, it lacks<note>’s granularity—notably the@respattribute to specify a mark’s agent.

These constraints complicate accurate representation of reading traces in practice.

While the resulting XML file could theoretically support a new namespace for Garfinkel's reading traces, the project deliberately works within TEI's existing framework - recognizing that new formal rules would create their own tensions between formalization and practices. Rather than developing new markup, we appropriate TEI's structures while documenting how practitioners negotiate their limitations, making visible the tension between formal representation and lived meaning-making practices. The project renders visible this fundamental gap: the slippage between formal representations of textual interaction and the indexical practices through which readers actually make meaning.

As experienced editor Angela Kump encoded Garfinkel's reading traces, she documented her negotiations - actively making ad hoc decisions about usage paradigms for specific TEI elements and attributes. The results can be seen here: Documentation and XML TEI File

Example of TEI Encoding

<pb xml:id="p5" n="5" facs="Seite00023.png"/>

<note xml:id="p5_n1" place="margin" target="#p5_s1" rend="pencil" resp="#HG" anchored="false">

<lb/>take apart

<lb/><del rend="strikethrough"><gap quantity="1" unit="word" reason="illegible"/></del>

<lb/>this metaphore

<lb/><persName ref="#DL">Lewis</persName>

<hi rend="underlined">only</hi>

<unclear reason="eccentric_ductus"/>

<lb/>as well talk like

<lb/><add place="above">This</add> of Hipouri walk

<lb/><del><unclear reason="illegible">like this</unclear></del> because

<lb/><persName ref="#DL">Lewis</persName> describes it

<lb/><unclear reason="eccentric_ductus">Carlhaut allding</unclear>

<lb/>the <hi rend="bracket">mentalistic

<lb/>cognitive</hi>

<gap quantity="1" unit="word" reason="illegible"/>

</note>