Incorporating Audio Data

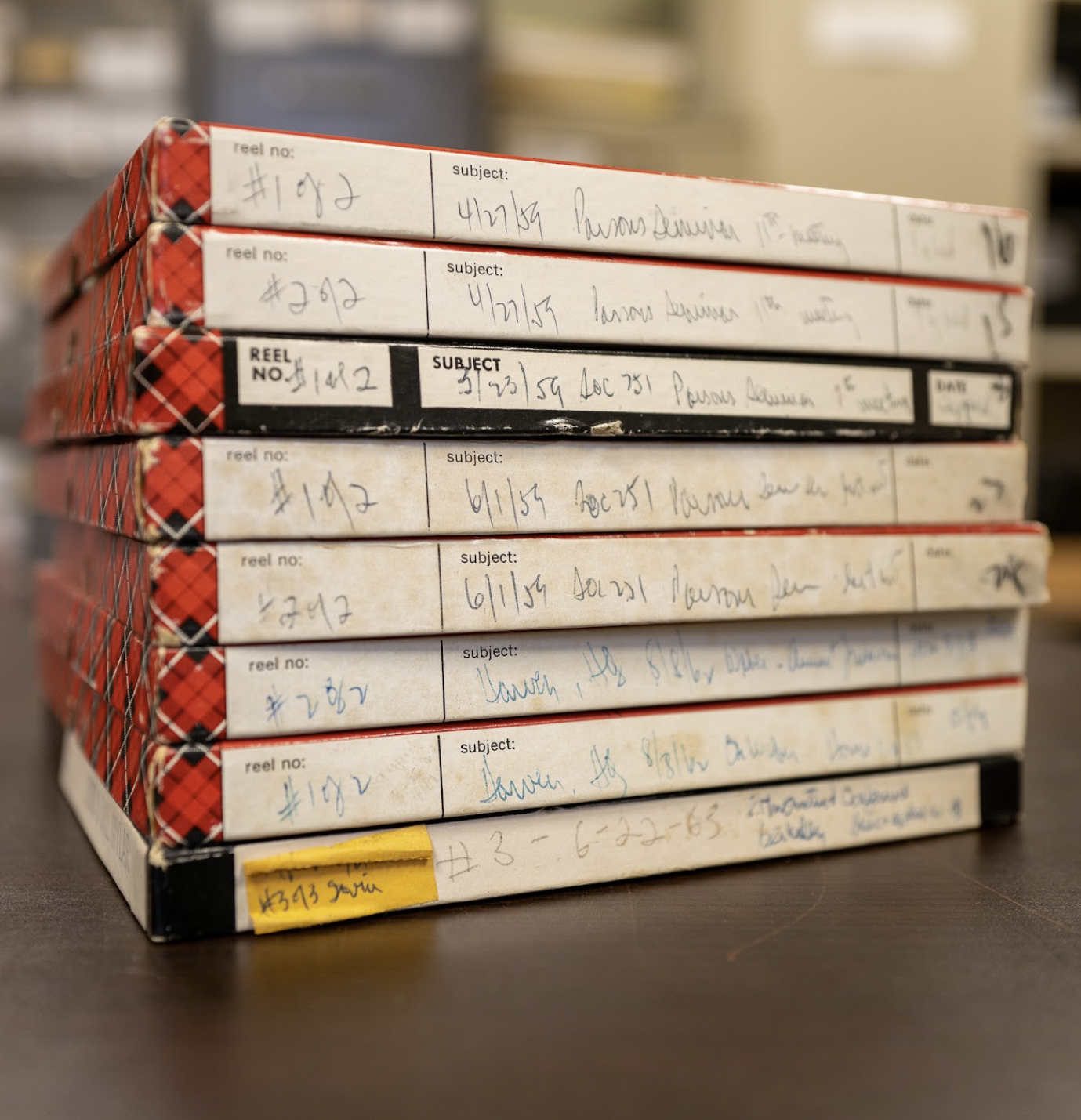

While the Occasion Maps papers at the center of this project do not themselves include any audio recordings, the issue of how to handle such materials emerged during the course of our work. This was prompted by the presence of several transcripts within the collection, which raised the question of whether corresponding audio sources existed. Collaboration with the Garfinkel Archive revealed that these transcripts likely correlate with a series of tape recordings already housed in the archive—many of which have been at least partially digitized. Although the digitization and integration of audio materials lay outside the formal scope of this project, this discovery sparked further investigation into the relationship between the transcripts and the audio sources. It also opened up dialogue with other initiatives that are addressing the challenges of incorporating audio data into digital scholarly editions. These exchanges have proven valuable in situating our work within a broader community of practice and methodological development. A report on the workshop where these discussions took place is available on the DH BUW blog

Audio in the Garfinkel Archive:

- 1831 digitised audio files

- approx. 3000 hours of recordings

- Types of recordings: University Lectures, Scientific Talks, Meetings with colleagues and students

- Types of Media: Reel-to-reel,Compact Cassette, digital memory cards

Audio Recordings

As part of the digitization process of the Harold Garfinkel Archive in Newburyport, MA, over 1800 audio files—amounting to approximately 3000 hours of recordings—were archived from a variety of physical media. A comprehensive collection of these recordings will be made available to interested researchers at the Harold Garfinkel Archive at a later date.

Garfinkel had developed a work method that placed significant emphasis on audio documentation. He routinely recorded nearly all of his seminars, lectures, and, in some instances, even his office hours and telephone conversations. In the specific case of his lecture series on Occasion Maps, each session was recorded in full. Subsequently, Garfinkel would enlist assistants and students to transcribe the recordings. These transcriptions were then submitted back to him for review. In several instances, students were awarded extra credit for this work—an arrangement explicitly referenced in some of the recordings.

The circumstances under which these recordings were made present certain challenges. Most were captured using small, consumer-grade tape recorders positioned in active lecture environments—spaces filled with students talking, moving, and interacting. As a result, the audio quality is often suboptimal. Many passages are difficult to decipher or, in some cases, entirely inaudible, complicating both transcription and scholarly interpretation.

Transcripts

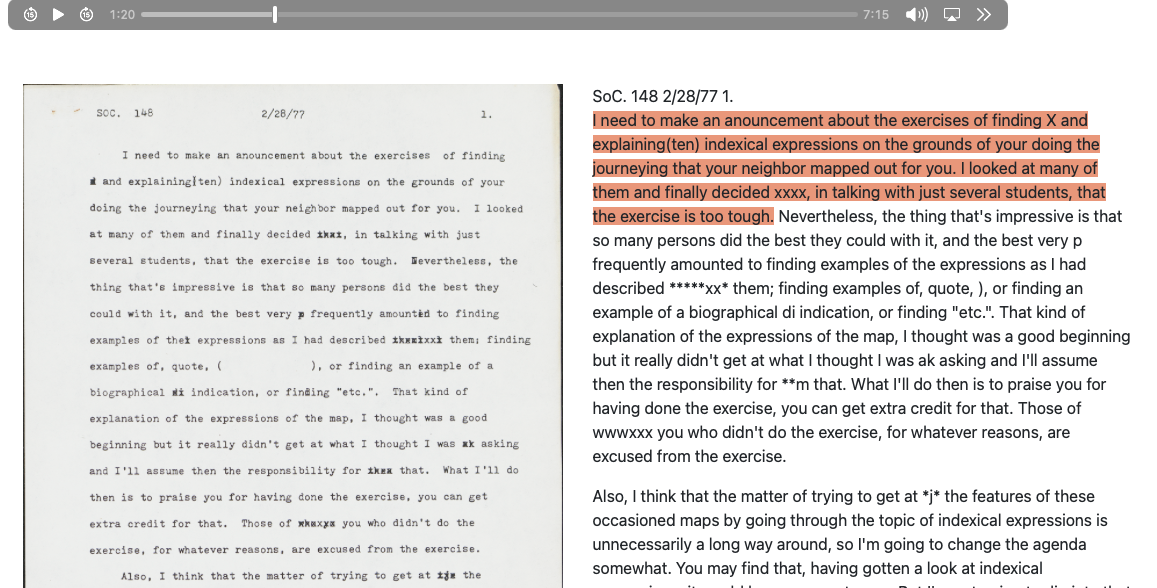

A long-term desrable goal would be to generate full transcriptions of the archived audio recordings, ideally providing users with synchronized access to both the audio and its corresponding textual representation. Where available, these automatic transcriptions could also be aligned with Garfinkel’s original historical typoscripts, enabling comparative analysis and enhancing accessibility.

For such an infrastructure to be both plausible and sustainable, an automated transcription pipeline would need to be developed. While a range of audio-to-text tools now exist—including commercial AI-assisted solutions—significant obstacles remain. Chief among these is the variable and often poor quality of the original audio. Many recordings suffer from background noise, low fidelity, and inconsistent speaker distance, making automatic recognition difficult.

Initial experiments using AI-driven transcription tools were conducted in 2023. Although notable improvements in transcription accuracy were observed over the course of the year, especially for low-quality audio, the results remained inadequate for research purposes. In most cases, the output was too unreliable to serve as a foundation for scholarly use. A further technical hurdle lies in the distinctive nature of Garfinkel’s language. His lectures are characterized by highly specialized sociological terminology and a unique conceptual lexicon, much of which is not represented in the training data of large language models (LLMs). For instance, the term “occasion maps”—a concept specific to Garfinkel and even niche within his own work—is frequently mistranscribed by LLM-based systems as “economical maps” or similarly unrelated phrases. This illustrates a common issue: in the absence of context or domain-specific training, LLMs default to semantically more common phrases found in their training corpus, leading to systematic misinterpretations of rare or idiosyncratic terms. Addressing these challenges would likely require domain-specific fine-tuning of transcription models, as well as the integration of custom vocabularies and speaker adaptation techniques. Such efforts, while promising, would demand substantial technical investment and interdisciplinary collaboration.“I have a lot of backlog of transcriptions from previous sessions of topics similar to the ones we’re discussing but i’m not going to be able to get to them but they may be [inaudible] to you but not in the present shape. The typist was instructed “Oh… just type what you hear”. They worked unsupervised and they are filled with all kinds of …crud. Whosoever volunteers to do an editorial job on a transcript will have [inaudible] in return for which you can have the further task, after it has been editorialized, and I mean heavily editorialized I’m talking “taking out the crud” For example if you have a page, in the beginning will be..its…like just the sort of thing we’re talking about now that will be pointless. That needs to be taken out. There is a lot of half-formed sentences. Umms and ahhs. Come on.. so it needs to be turned into scripts of sorts.”

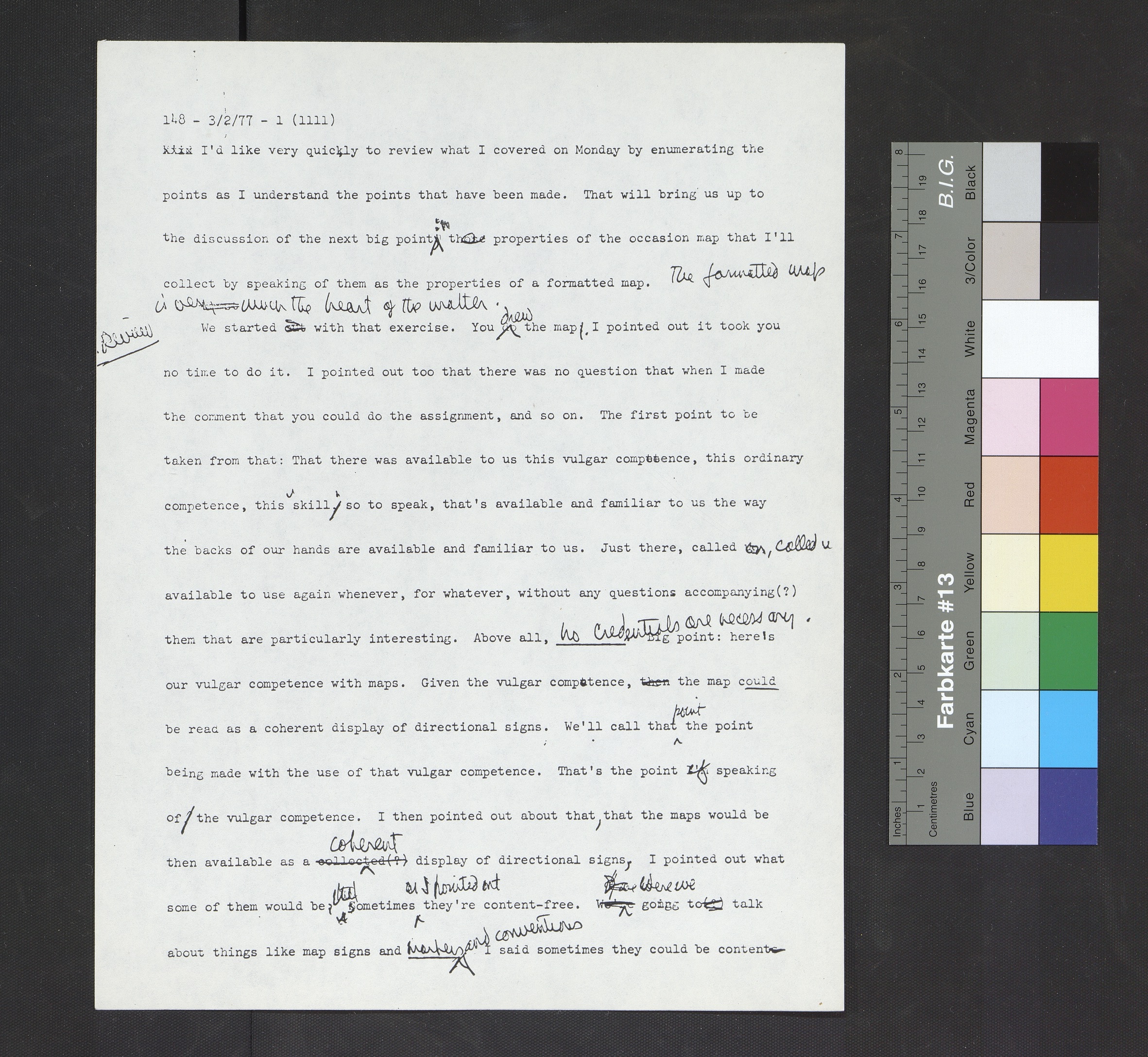

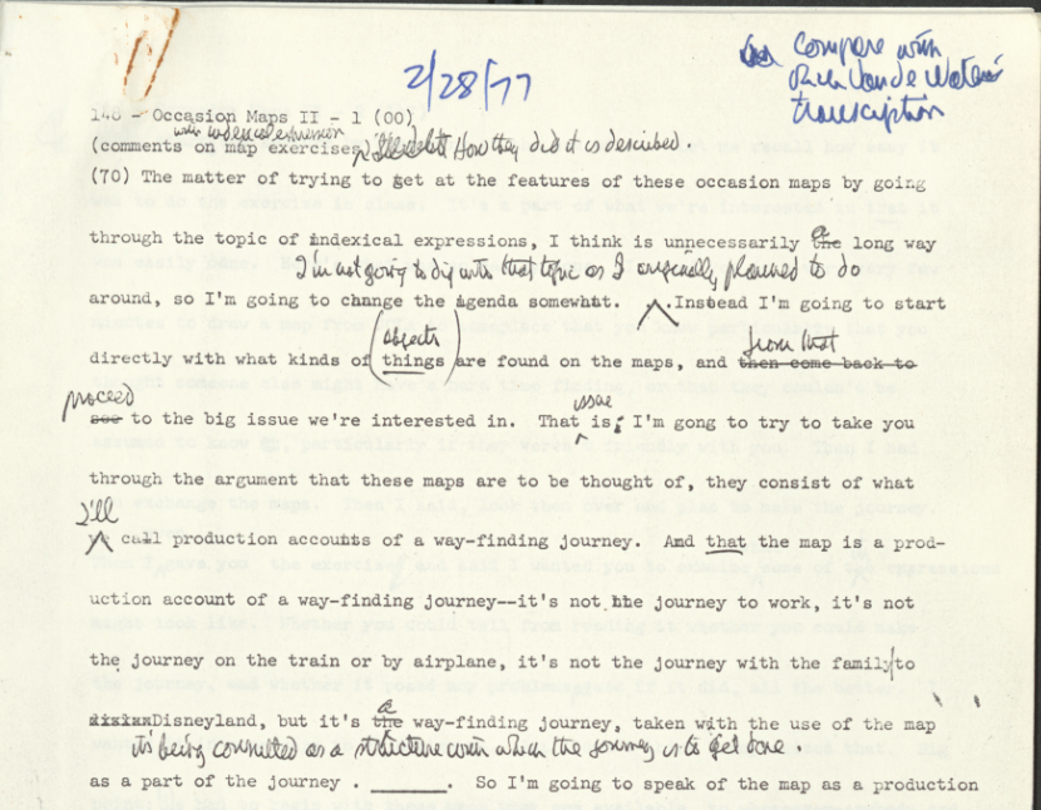

Typoscripts

These typoscripts, found in the collections, give further insights into Garfinkel process, as they can be found in different states of editing and revision. When looking at the transcript three groups can roughy be recognised that vary in terms of completeness and accuracy to the source audio. The first group are relatively raw transcriptions that closely follow the audio but have obvious lacunae and gaps left by the transcriber when they could not make out utterances in the audio. Some have omitted small utterances, aside or preliminary remarks that are present in the audio but have been left out in the transcript. Another group are these raw trasncripotions with added handwritten annotation and revision remarks, likely by Garfinkel or an assistant. These were sometime made in order to fill graps in the raw transcriptions and in some cases to reorder and add thoughts and explanation no in the audio. A first hint, that these transcriptions were used by Garfinkel to further work on this ideas and to bring the transcript closer in form and content to a research paper. A third category a typoscripts is apparently yet another step further along in the edition process. The typoscript do not follow the audio anymore but are restructured and rewritten form likely based on previous transcripts. These reorderd typoscriopt were not the end of any process but include further handwritten revisions.

Proofs of Concept