EAD Finding Aid

During the project an EAD Finding Aid was produced for our digitized documents. This page documents the methology and background of this process. The resulting Finding Aid was published as an EAD-XML File on Zenodo. A simplified PDF Version was also created using Midosa.

The initial digitization efforts are accompanied by the creation of descriptions for every scan, following a naive approach and constituting the objects with a bottom-up principle (see Digitization). To observe the differences between this naive approach and formal archival practices, it is essential to adhere to an established cataloging standard.

The catalog, developed based on archival best practices, was researched and executed by Angela Mascheck. After a thorough examination of existing best practices, Resource Cataloging with Authority Data in Archives and Libraries (Ressourcenerschließung mit Normdaten in Archiven und Bibliotheken - RNAB) was selected as the main framework. This version 1.0 was published in January 2019 by the Austrian National Library (Vienna), the Swiss National Library (Bern), and the Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (Berlin), showcasing a collaborative effort and multi-institutional support. All recent developments, such as RDA (Resource Description and Access) and RiC (Records in Context), have been incorporated into the RNAB guidelines, making it the industry standard.

RNAB considers technical solutions, but it is not a technical framework to build datasets. Instead, it serves as an intellectual guideline, usable, for example, as a plain textual description for a given collection. To realize the finding aid in a machine-readable format, a technical standard like Encoded Archival Description (EAD) is necessary. RNAB maps its rules to the fields of EAD to facilitate indexing at the technical level. But before that an indexing plan has to be determined.

RNAB: B-1 Determine and Organize

The RNAB recommendation to create an indexing plan was followed. In doing so, the existing order of the collection was maintained; the resources were not organized thematically, as is the case with other estates that are, for example, structured by works, correspondences, life documents, and collectibles. The question of Garfinkel's knowledge representation was guiding, with the assumption that statements about the work process of the estate holder could be made if the existing order was preserved. However, at that time, it was unclear whether the existing order was already established by Garfinkel or by the estate administrators.

It was observed during the processing that thematically related documents were stored together, and a chronological order was evident within the folders. The cataloging levels "Fonds" (collection), "Series" (sub-collection), "File" (file), and "Item" (individual resource) were taken into account.

RNAB: B-2 Indexing

In RNAB, 'Levels of Indexing' can be understood as the hierarchical framework that describes the physical order of a given collection. The mapping of the hierarchical concepts of RNAB to Occasion Maps is as follows:

- Collection Level: Occasion Map Papers

- Sub-Collection Level: OM1, OM2, OM3

- File/Compartment/Envelope Level: Folder, Compartment, Envelope

- Individual Resource Level: Sets, Nosets (Transcripts, Notes, Academic Works, Seminar Papers, etc.)

It became apparent during the processing that another level under the individual resource was useful in some cases. For example, Garfinkel's student seminar paper (individual resource) consists of texts, maps, scripts, etc. (additional individual resources). Fundamentally, the RNAB does not specify how detailed the depth of processing should be. It depends on various factors such as the significance of the collection, the personnel capabilities of the holding institution, and the interests of the users. This led to different levels of processing per resource during cataloging, as not all sub-resources contained clear references. To stick with the example above, students submitting a seminar paper might only include a map. The reflective text of the assignment is a marginal note on the map. Therefore, the varied handling of the assignment by students resulted in uneven granular directory structures. This issue also arose from the decision to maintain the physical order of the estate. The conflict required an answer to the question of whether two individual resources (text and map) or one physical individual resource (sheet with text and map) should be recorded thematically. Each resource should be associated with a digitized version, which was the reason to continue prioritizing the physical order.

RNAB: D Elements of Indexing and EAD - a conclusion

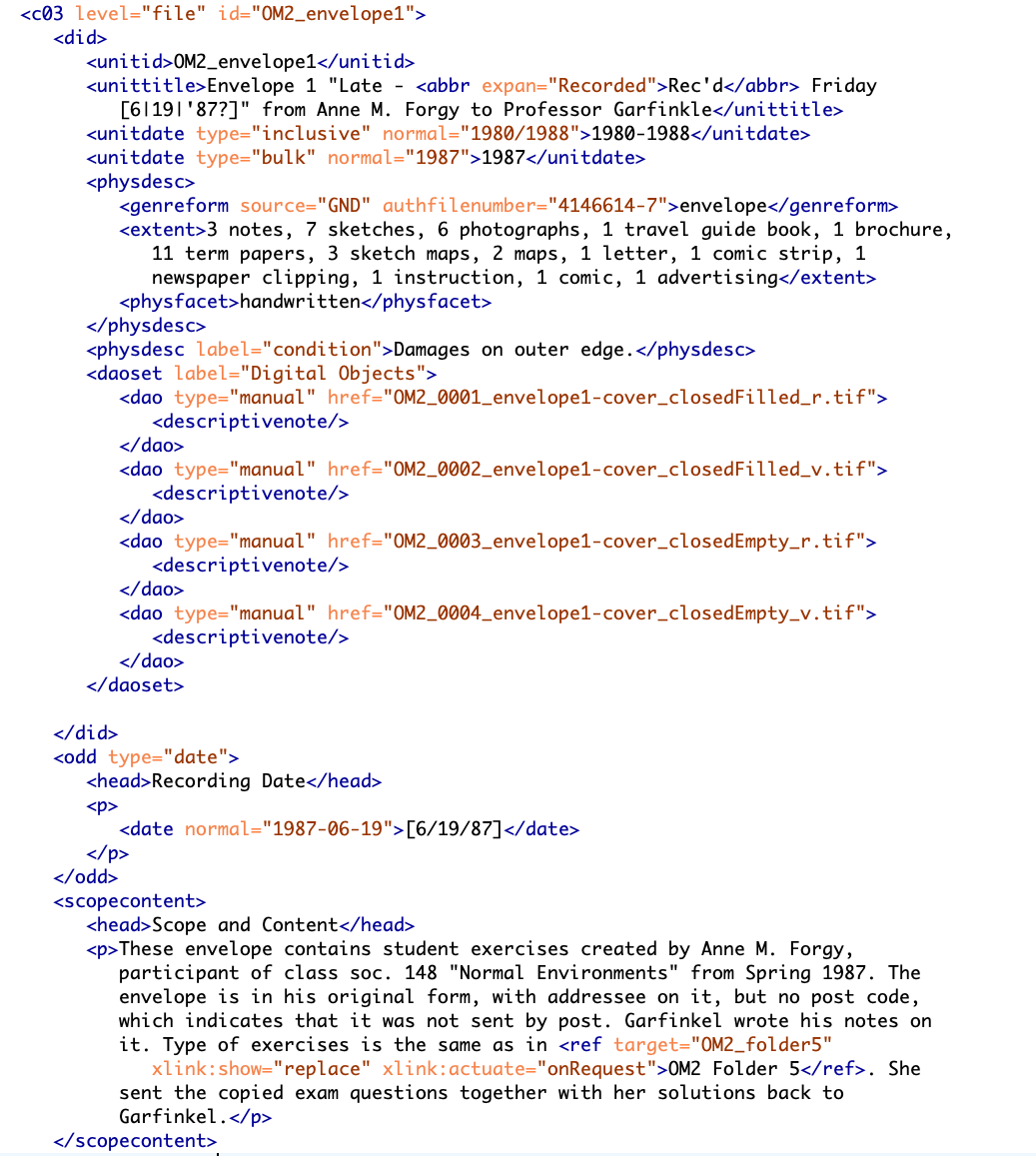

In sections D-1 to D-22, RNAB defines the necessary elements for indexing. These elements record 'things' relevant to the collection's description. Additionally, RNAB provides a mapping of these elements to existing technical standards, including EAD. Informed by this mapping, an XML file is created using the EAD standard, adopting the profile of the German Digital Library (DDB: Deutschen Digitalen Bibliothek). The task involved a considerable amount of micro decisions, both intellectually and technically.

Most of the troubles can be defined as encounters with 'how to formalize?' One particular paragraph, as her work comes to an end, describes well how the recording and indexing process starts with confidence but creates a deep uneasiness:

“I must not adhere to physical order because the structuring is inconsistent. However, I do not have the intellectual authority to claim that the "creator" is wrong (the main problem). I only realized this in the process of cataloging when I observed different structures. The categorization into sets led me to anticipate a consistent and coherent division into units by the creator. This is, of course, not the case and was a misconception. There are multiple creators, and there are different ways of thinking. Even with just one creator, there are differences in treatment. In a way, I could observe this in myself, as I implemented different solutions for the unit problem during work by adapting my "thinking." The only way to establish uniformity would be to deviate from the existing order (or physical materiality - in the case of digitized materials, digital ones) and thus grant myself authority as the guidebook creator. Alternatively, not detailing the units but indicating on the overarching item level which objects are included, without listing them in detail, is another option.”

This uneasiness is awfully similar to the main trouble that H.L. Wood encountered in his ethnomethodological study on Zatocoding, in which he coded 500 items with 44 descriptors (tags). He details his encounter with 'troubles' in great detail in his paper from 1969. Like Angela Mascheck, he discovered the almost impossible nature of uniformity and accompanied uneasiness. He also experienced how the solutions are context-dependent, time-bound, and personal:

“None of the descriptors or the items to be coded, the corpus, are stable. Both shift in meaning as I read and re-read them and use them, as I have experiences and thoughts.... It suddenly hits me as an impossible task. I am in a flow and the task demands stability of descriptors, library and coder/me.”

„Swarms of meaning with nothing to count on except that I will be able to make some sense. Never the sense as that might seem to imply a "correctness" beyond the here and now perspective. This is vertigo. Epistemological dizziness.“

This aspect may be one of the most crucial realization in the project. Although the digitization and recording efforts aim to establish a supposed objectivity, without having authority and authorship during the execution process, it seems to be an almost impossible task to achieve. Resisting the not objectively formalizable nature of practical everyday objects understandably produces uneasiness towards expectations of objectivity.

nterestingly enough, as Wood states “the coding got done and continues to get done”. As proven by countless projects in this field. How this is so appears to be a feature of object constitution (see Digitization) in which the results hide the process.